Towards a Poetics of Partnership

Vision

Local and planetary relationships that reflect love as well as need for 'goods and services'.

A vision describes an ideal state of the world, an aspiration that relates to our traditional norms and evolving concepts of justice, rightness, who we truly are and what we would like our children’s children to inherit. A world without war and hunger. Flourishing fish, forests and wildlife.

Science can tell you a great deal about what is, but nothing about what should be.

(Albert Einstein)

Principles connect a state of the world as it is, to a vision of what it should be. Principles are linked to outcomes. In general, science is more comfortable with measurable outcomes such as the number of salmon that should be allowed to escape the fishery to spawn than with high level principles (Jamieson et al. 2010). Principles such as gratitude, humility, repentance, atonement, compassion and the Golden Rule are generally taken to be the province of religion. The idea of ‘higher’ principles is however profoundly unhelpful. If all the Irish had died in the potato famine, there would be none left to muse on spiritual values. In either case, the work of implementing a principle can be understood as a virtue, for example, the “epistemic virtue” of deep or compassionate listening (Carlson 2007; Fricker 2007).

Welcoming

The core values are welcoming the awe, mystery and fascination of different ways of understanding and being in the world, as opposed to the dominance or "epistemological sovereignty" of religion, science or economics. We see different ways of understanding and being in the world (ontologies and epistemologies) as enriching rather than exclusive. We are open to ideas and ways of communication that are incommensurable with our formal training. We will be watchful for things which our upbringing has not equipped us to recognize. We seek to recognize rather than assign values from some objective or dispassionate viewpoint. We anticipate that the epistemic virtue of active or compassionate listening to humans and non-humans will reveal what we seek together as opposed to the language of individual discovery, invention or creation.

Openness

Openness demands constant watchfulness for things that our upbringing might not enable us to perceive. Openness is deliberately turning toward things that might seem alien or unsettling to our notions of how the world is or should be. Openness and welcoming are set against tolerance, which is essentially condescension. It is as much as to say, "You can have your strange customs, odd clothes and stinky food, we know better, but if you stick around long enough, you'll learn to be almost like us." Tolerance is better than bigotry, but falls miserably short of welcome! Someone I would love to credit said that we should treat the 'incommensurable' as a gift, not a threat.

Creative Justice (Tillich 1960) seeks to reunite those separated by forces and structures beyond their control, such as the realms of science and religion, or fishery sectors set at odds through the politics of scarcity (Haggan 2000). The motivation is love—a passionate desire for the flourishing of the world, its people and creatures and commitment to conserve and protect them against depletion and extinction. Creative justice greets different knowledge traditions as awesome, mysterious and fascinating, as opposed to any attempt to ‘harness’, ‘capture’ or ‘integrate’ one into another. This recognition that myths, maps, models, equations, parables, ceremony, music and other arts enrich rather than contradict has been described as "cognitive justice" (1992; de Sousa Santos 2007), epistemic justice (Fricker 2003) and epistemological pluralism (Miller et al. 2008). Creative, cognitive and epistemic justice challenge us to conceive the inconceivable (Povinelli 2001).

The Language of Love

The gift that ordinary people bring to environmental review is the language of love for lands, waters, plants and creatures to which they are deeply connected and committed to cherish and protect. The powerful response to such language when used by Indigenous spiritual people (and a growing number of mainstream religious leaders) indicates that it belongs to us all.

Unfortunately the words of love and relationship we use in our private lives are not part of the project review or management lexicon. We cannot ask scientists to bring Indigenous and religious concepts of covenant and relationship with non-humans into their work. We can make the conversation more complete by bringing Indigenous spiritual leaders, religious leaders, artists—poets and painters, dancers and filmmakers—into the work of review of projects such as Enbridge, industrial salmon feedlots and fisheries subsidies

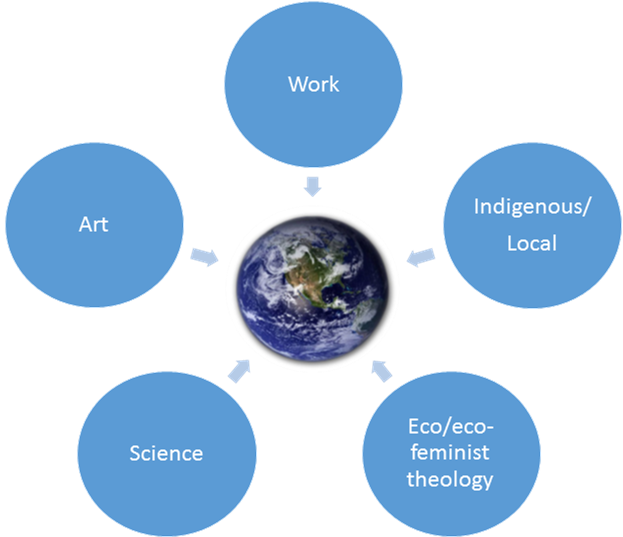

We will bring Aboriginal spiritual and world religious leaders and artists together with scientists to bring the language of gift into a new relationship among the disciplines that reflects the human dimensions of love and gratitude towards animals, plants, lands and waters alongside the need for the 'goods and services' they provide. Haig-Brown (1992) suggests that research progresses from formal conversation to informal chat to stories. Figure 1 identifies the main elements of the conversation. Planetary and local concerns illuminate and compel connections that did not previously exist. We hope that multiple 'stories' can increase awareness and point to remedial actions which may not be apparent to the spheres in isolation.

Approach - A Poetics of Partnership

The poetics of partnership will take many forms including visual arts, music, rap, film, poetry, scientific papers... It is vital that our work recognize the validity of diverse ways of understanding and being in the world, the epistemic virtue (Carlson 2007; Fricker 2007) of deep or compassionate listening to perspectives currently deemed inadmissible, “incommensurable” (Povinelli 2001), “discrepant” (van Zyl 2009), or immiscible (Gould 1997). In this spirit of epistemological pluralism (Miller et al. 2008), and with no intent to pre-empt other luminous and powerful symbols that will emerge, we offer the initial symbol of a riverside tree, where both the convergent roots and the confluent streams represent the meeting of different ways of understanding and being in the world (Figure 2).

The flow of water and nutrients from bedrock through soil to roots to the trunk, into branches, the birds and insects, is a quickening dance of spirit fueled by sunlight falling on the leaves. The roots are fractal, from individual people and creatures to families and ecologies through thickening roots of Aboriginal, religious and aesthetic traditions, natural and social science and the dedication of ordinary people. The roots of a riverside tree may shelter a salmon—an ancient symbol of wisdom in Aboriginal and Irish tradition. As a verb, the tree embodies belonging and relationship in ways that ‘ecosystem’ and ‘social-ecological system’ cannot.

Spiritual, religious and aesthetic values have re-entered, or more correctly are troubling the resource management sphere. A growing ecological economics literature identifies 'intangible' values as equally or more important to many people than money. The standard response is to point and scoot, i.e., to cite lists in classic studies (Costanza et al. 1997; MEA 2003; de Groot and Hein 2007) , then state that these values are 'difficult to measure' and continue putting dollar values on 'ecosystem services' as a way to influence decision-making. A second response is to document how spiritual values contribute to long-term sustainability in remote and romantic places, but fail to make a connection to the streets of Shanghai, London, Paris or New York.

What: A multi-year project to design environmental impact assessment and management processes that reflect love—in the sense of protecting and cherishing species and places to which we are committed—as well as our need for 'goods and services'. The long-term goal is to reinstate the language of belonging where what we now tend to see as 'resources' are recognized as relations—as ends as well as means.

Stories Matter: The stories we inherit and the stories we tell ourselves about who we are and how we relate to all of creation matter most of all. Myths, music, models, parables, equations, are all ways to make sense of complexity. The internal contradiction in the term 'true story' points to the fact that a metaphor both is and is not the thing that it points to. A fundamentalist is someone who believes that their story has a lock on truth, someone who wouldn't recognize a metaphor if it jumped up and bit them.

Our project has its roots in a time when the social, economic, intellectual, artistic and spiritual dimensions of existence were interwoven. Fast forward to the ecological crisis and we find that the language of love and relationship has little or no place in 'resource management'. This problem is recognized by the 42 leading scientists and 270 world religious leaders who signed the Declaration Preserving and Cherishing the Earth (Sagan 1990). Scientists from Gregory Bateson to EO Wilson and the Pew Oceans Commission have called on religious leaders to pay attention to the ecological crisis. World religious leaders have responded in numerous declarations. Eco-theologians recognize the need to extend scripture's message of care for poor, oppressed and marginalized humans to depleted species and degraded ecosystems (McFague 1993; Boff 1997; 2013). Programs such as the Alliance of Religion and Conservation are working with communities to address ecological and human poverty. Ocean scientists from Jacques Cousteau to Sylvia Earle invoke love of the sea as critical. It is notable that in all of these examples, researchers are speaking outside of their professional output.

Why (Rationale): People, animals, plants, lands and waters shaped and reshaped each other in conversations that took place over thousands of years. Economic, social, intellectual, spiritual and aesthetic dimensions were woven into all aspects of existence. Over time, Enlightenment science and mission Christianity confined the spiritual and religious dimension to the private sphere. Art tends to be stigmatized as a cost to taxpayers, something for elites who frequent galleries, orchestras and museums, but of little or no relevance to ordinary people. In consequence, non-humans are seen as 'resources' that contribute to sector economics and GDP. 'Resources' are measured in the accounting terms of 'stocks and flows', managed through monitoring, surveillance and control. They do not merit moral consideration. This political-level separation does not apply to the scientists and managers who tend to be passionately committed to the well-being of the species, places and people in their charge. It does not apply to the public where the conversation with plants and animals can be seen in the diversity of gardens on a city block and in dedication to conserve species and places.

Play is at the heart of our work. Play combines absolute attention with cooperation and openness. Play adds the element of delight to the attention of research, prayer or worship. Interweaving play into collaborative work is a gift. It requires a messenger of joy to bring to life activities that are supposed to break down barriers, but can actually deepen self-consciousness and discomfort.

Dimensions of knowledge

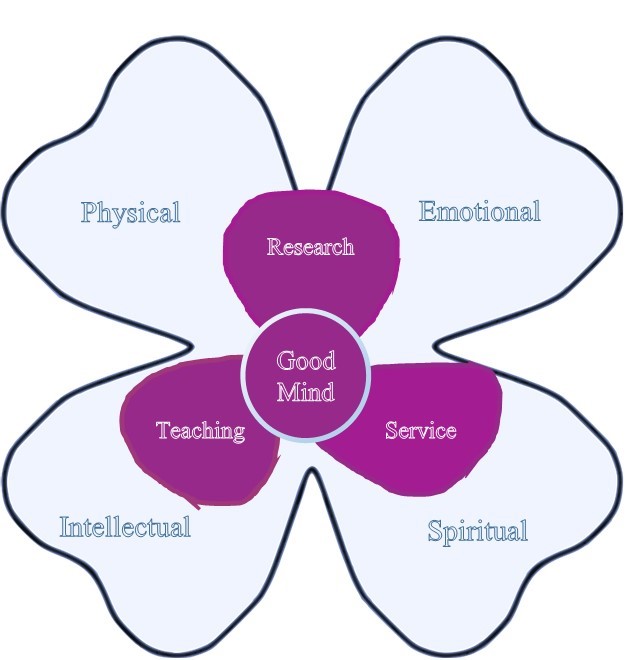

Our structure for events and products interweaves the four dimensions of wisdom—physical, emotional, intellectual and spiritual—recognized by Aboriginal people as "necessary for a fully-embodied way of being in the world” (Simpson 2011:94) and in the scientific concept of biophilia or love of nature (Kellert 2005) (Figure 3).

Compassionate mind signifies that a person has intellectual and heart knowledge that is given and received in relationships with human and non-human others. A "good person” is someone who has intellectual and heart knowledge (Holmes 2002:46; Archibald 2008:47), which is relevant and put to use in their community. The compassionate mind combines physical, emotional, spiritual and intellectual learning with humility, truth and love (Lightning 1992). 'Good mind' resembles the classic university mandate of research, teaching and service, but differs in that learning is reciprocal and intellectual knowledge has no special privilege.

Spirit and spirituality

Spirit, we understand as the recombinant power of the universe, forming, dissolving and reforming from the first instant of creation till now and into the deep future. English is a noun-based language; Spirit is the verb that connects, that manifests itself in evolution and all aspects of human endeavour and creativity. Spirituality consists in dedicated attention to the web of spatial, temporal, local, regional and global relationships, so as to strengthen those that lead to flourishing and unpick those that are destructive. Spiritual practice is thus as integral to management and conservation science as it is to art and religion.

How: We propose to focus on processes where intangible values are poorly represented, if at all. Examples might include global fisheries subsidies in excess of $22billion which make 2015 food security targets impossible to reach, the WTO, EU and other decision-making processes. Inclusion of a more complete range of values and perspectives could also contribute to better decision-making in the vexed matter of the Canadian tarsands and associated Keystone XL, Kinder-Morgan and Enbridge pipeline proposals. The Enbridge review accepted by the government of Canada in June 2014 has been deemed flawed by numerous scientists. We contend that it was also incomplete. That however well qualified to consider quantitative harms to people and environment, there were entire dimensions of moral concern that the review panel was not qualified to consider (Brunk 2004).

This is not a problem of language. The scientists, economists and engineers on the panel are all fluent in the language of relationship when it comes to their family relationships, their gardens and sacred places. It's just that their gift of dispassionate analysis has denied this language in their professional roles. The solution is to bring the people whose language this back into the processes (Haggan 2011).

Products and dissemination:

Products will include musical performances, scientific papers, visual and performance arts, video, poetry, rap and other media. Our writers and illustrators will contribute ideas to one or more children’s books.

Open source: All products will be open-source available through a project website with multiple entry points (Figure 4):

Anticipated outcomes:

⦁ A coherent case for inclusion of spiritual, moral and artistic perspectives with natural and social science;

⦁ Design of a process to include multiple voices in decision-making;

⦁ A strong voice for more rather than less inclusive review processes;

⦁ The start of a multi-year process to expand the range of values in environmental impact assessment, that may in time lead to change in national and international law;

⦁ Iconic images of the poetics of partnership to tell a new story of human/planetary relationships;

⦁ Robust concepts of eco-spiritual intelligence and the planetary sacred;

⦁ Two new, multidisciplinary courses:

i. Spiritualities of science, art, religion and work in environmental practice; and

ii. The match (or dissonance) between neoclassical economic and Indigenous and religious concepts; and

⦁ Peer-reviewed contributions.

Long-term sustainability:

The ecological imperative to rethink our relationship with the planet suggests that such a group might provide advice to government and industry in the form of process design and expertise. It is also possible that forward-thinking universities might consider expanding their 'resource management' schools to include aesthetic, spiritual and religious perspectives alongside natural and social sciences and engineering.